March is Women’s History Month, and Fulton County was once home to one of the most revolutionary early businesswomen in the state. Rose Knox’s appreciation for her employees, innovative business practices, and generosity to her community earned her the sobriquet the “Grand Old Lady of Johnstown.”

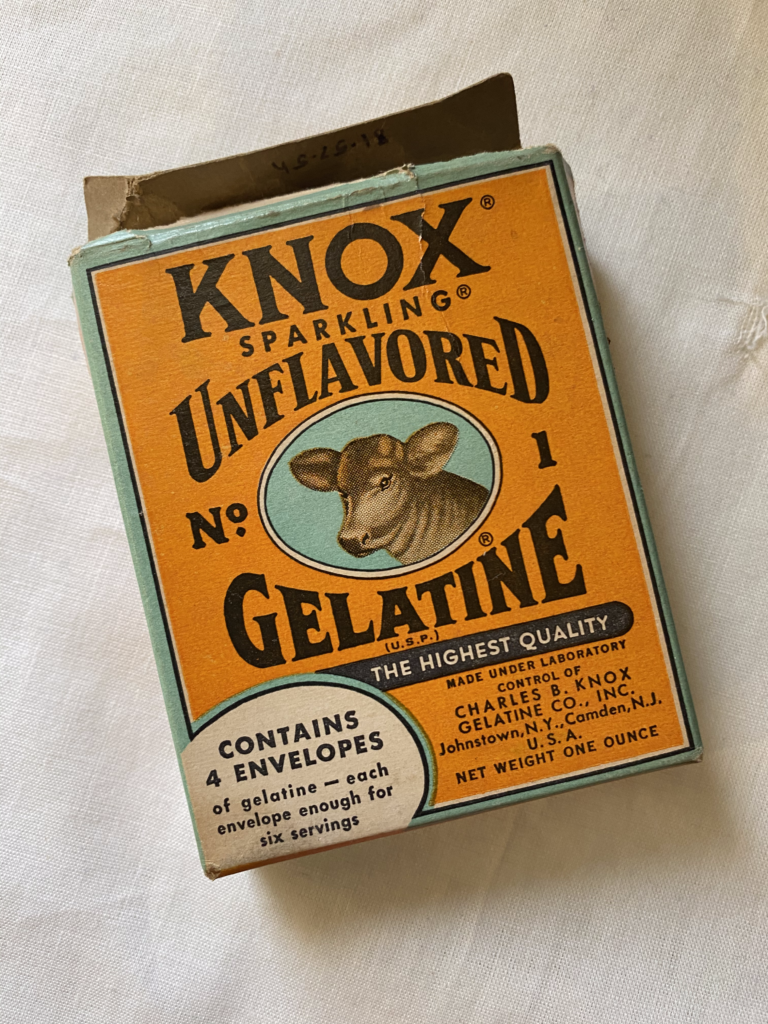

Rose Markward Knox was born on November 18, 1857 in Mansfield, OH. She came to Gloversville in the 1870s to work in the glove industry, where she met her husband, Charles, at a dance. The couple married in 1883 and moved to Newark. The marriage was very much an equal partnership. Charles, who worked as a successful salesman in knit goods, often discussed business with his wife. Rose was given an allowance to purchase food and other items necessary to run the home; any money left over was her own to keep. If Charles borrowed money from this fund, it was treated as a business transaction and expected to be repaid. It was with the $5,000 that Rose had saved with smart spending and household efficiency that allowed the couple to purchase a defunct gelatin plant in Johnstown. In 1896, Knox Gelatine was established.

When the Knoxes began their business, making gelatin was time-consuming. It was a long process that required boiling beef bones for hours. An improvement was made with the development of gelatin sheets, which still required soaking to soften. But in 1889, Charles Knox developed a granulated gelatin for everyday use. Rose was an avid cook and developed many of her own recipes. It was good business, too, to write them based around the ingredient of gelatin. Her first recipe booklet was published in 1896 and was a staple giveaway in grocery stores. “Mrs. Knox says…” was a common phrase in their advertisements.

By the time Charles died unexpectedly in 1908, the Knox Company also owned Spim Soap, Ointment, and Tonic, a small hardware store, and a power company. After Charles’ death, it was expected that Rose would sell the business or hire a manager to run it, but out of concern for the future of her sons, she did the unthinkable: she took her husband’s place and ran it herself. On her first day on the job, she permanently closed the back entrance to the plant, where women employees would enter. “We are all ladies and gentlemen working together here,” she said, “and we’ll all come in through the front door.” Under Rose’s management, a 5-day workweek was implemented and employees also received two weeks of paid vacation and sick leave, entirely uncommon for the time. Mrs. Knox didn’t have to lay off a single employee during the Great Depression, thanks to her smart cost cutting – in fact, the business grew at a rate of 5% per year throughout the Depression era.

During WWII, Knox Gelatine developed several recipes and published new recipe booklets to help home cooks make the best out of food rationing. One such booklet published in 1942, called Don’t Let Butter Rationing Scare You!, introduced a recipe for “butter extender.” With some Knox Gelatine and milk, any American woman could turn ¼ pound of butter into ½ pound of butter spread. Add a little food coloring to help it look even more like real butter. Mrs. Knox ensured wartime housewives: “You and your family are certain to be delighted with the rich, buttery flavor of Knox Spread. (You’ll also be happy to know there’s real good food value in it for them).” The booklet also contained recipes in which to use your Knox Spread, some of them from the company’s test kitchen and others from magazines like Good Housekeeping, “who are all enthusiastic about Knox Spread,” Rose assured. The company published several other wartime booklets, like Meatless Main Dishes and Leftover Hints (including classics like coffee jelly and a fish mold) and How to Be Easy On Your Ration Card (make some sponge pudding or the ever-popular tomato jelly for the family). The company was already touting the nutritional value of its pure protein gelatine, so it was certainly a selling point during the war when people were concerned about ensuring proper nutrition with rationed goods. “Knox contributes real protein value to your desserts and salads,” the booklets read, “and will also help stretch your rationed foods.” Check out a scanned copy of the butter rationing cookbook here – and if you’re brave enough to try a recipe, please share it with us on Facebook!

Under Rose’s leadership the company’s laboratory developed the first pharmaceutical gelatine, precursor to today’s gel caps, as well as a “plasma extender,” an intravenous blood plasma substitution used during the war. She was generous to the citizens of Fulton County, providing donations to build the Knox Athletic Field and the library at the junior high school named in her honor; she attended graduation every year and gifted each graduating student a rose – a tradition that was still going strong when I graduated from that school in 2001. She also established a home for elderly women, assisted with the restoration of Johnson Hall, and gave donations to a variety of places of worship, regardless of denomination. Though she handed over running the business to her son James in 1942, Rose Knox remained the chairwoman of the board of the company she helped establish until her death in 1950. She is buried in the Knox family plot at the Johnstown Cemetery.